About |

|

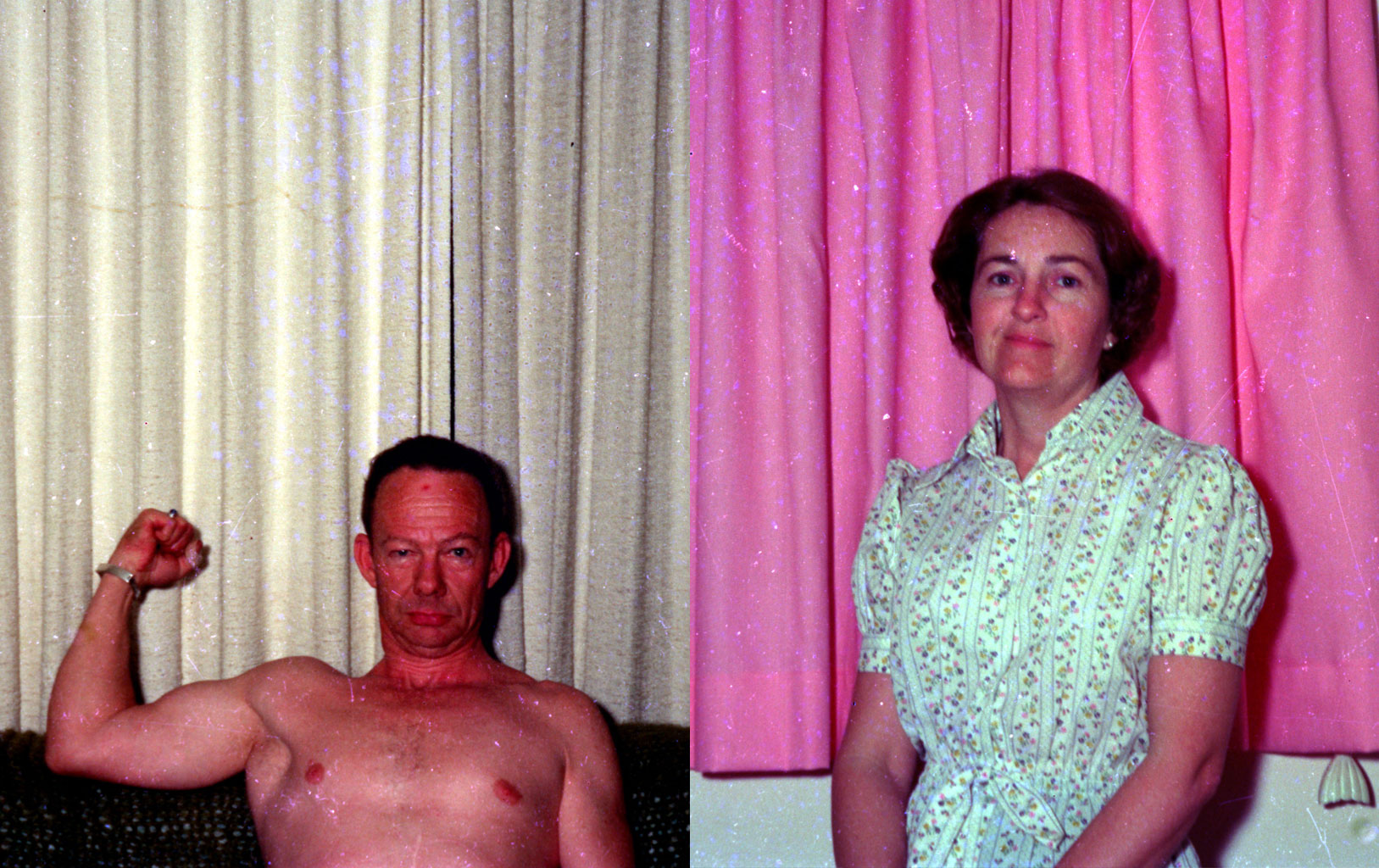

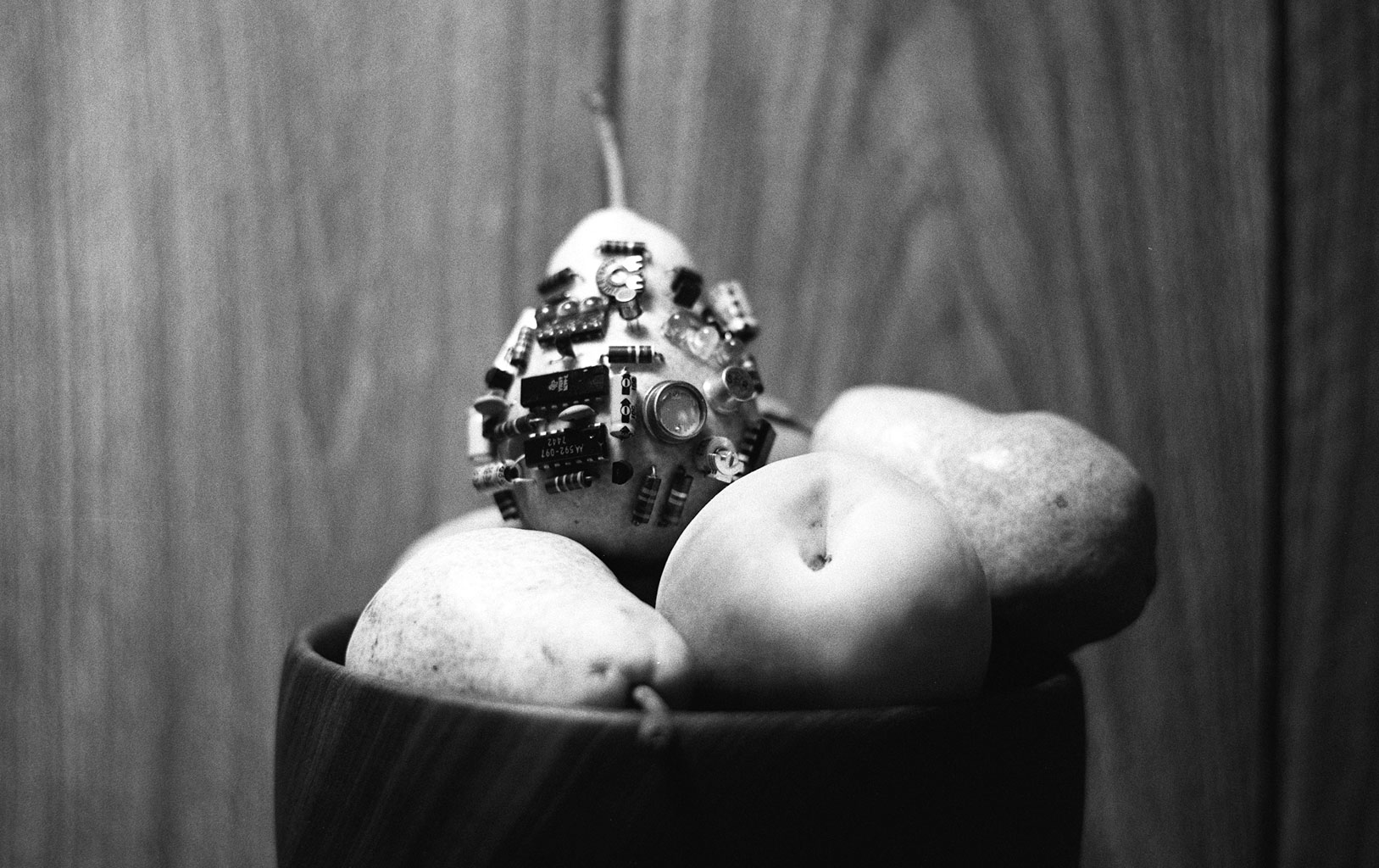

| Creativity When I was around ten years old growing up in Colorado my parents gave my sister and me each an allowance of 25 cents a week. In addition to my allowance I also mowed lawns and shoveled snow for money and my sister babysat. But my mother made an astounding gesture after my father died when I was twelve: she allowed me to spend as much of her money as I needed on my two favorite hobbies, photography and electronics, even as she went back to work and struggled with money herself as a single mother. Decades later, after university and working as a film and theater production manager in New York City for several years, I quit accepting jobs for the better part of a year and made a sixty lens camera by hand in the kitchen of my tiny apartment on the Lower East Side. After I finished it, completely broke and having been kicked out of that same apartment by my then girlfriend, I called my mom to thank her for supporting my interests as a child and for instilling in me the confidence to follow my passion and to become an inventor. To my surprise, instead of sharing my excitement, she started crying. When I asked her why she sobbed, "Because I think I ruined you!" One of the problems with creativity is that it's often difficult for others to comprehend it let alone to anticipate any future value that might be derived from it until after it's been validated by a perceived objective external authority. Five years later, in 1999, that same sixty lens camera was collected by the Smithsonian Museum of American History for its permanent photographic history collection. It was my second contribution to a major American museum, the first being a 16mm black & white narrative student film that I directed when I was an electrical engineering student at the University of Colorado, a homage to D. W. Griffith that I filmed and edited in the manner of his short silent films for the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company in the early 1900s. That film was screened for Lillian Gish, the lead actress in Griffith's 1915 film The Birth of a Nation, and was acquired for the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1988 when I was twenty five years old. After my father died my mother was worried that I would become depressed. She could see how I threw myself into my hobbies and she responded to that by encouraging them. I became depressed anyway, but as a result of her encouragement and sacrifice I developed a strong sense of identity and accomplishment as a photographer and an engineer while I was still a child. This was in part because I took both of those pursuits seriously and enjoyed them without any need for external validation, but it was also because it was clear to me that my mother wanted me to excel at both of them and that it was therefore my obligation to do so. As a result I grew into an adult that had an intense need to prove that my mother was correct to believe in me, which in turn gave me a great sense of joy and confidence in my own efforts and accomplishments in those two domains as I made my own way in this world. Abraham-Louis Breguet's father died when he was eleven. His mother remarried his father's cousin, an accomplished watchmaker, and young Abraham-Louis was thrown into the family business. Based on the dynamics of paternal loss and maternal love that I experienced as a child and the effect that those dynamics had on me it's no surprise to me that Breguet was able to synthesize technical and aesthetic creativity as well as he did and excel at watchmaking. If only his father could have known... |

|